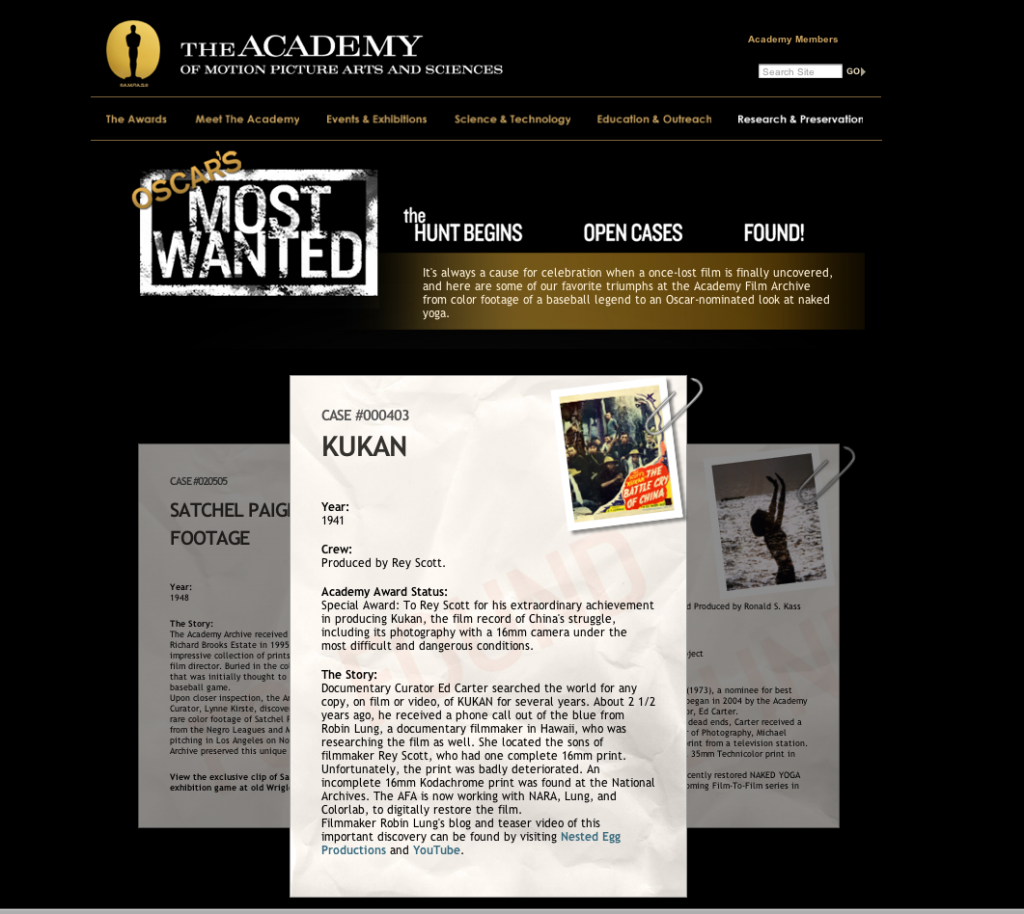

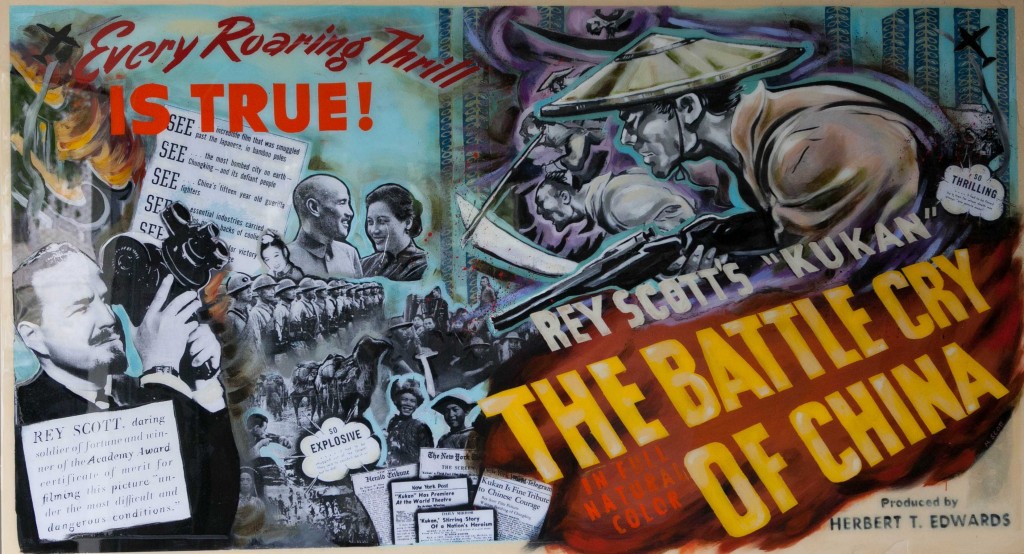

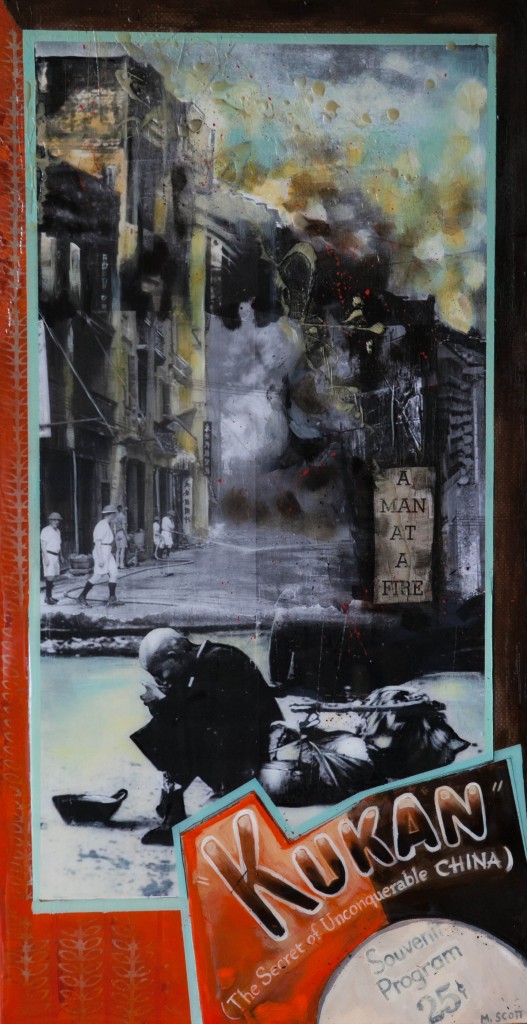

Many of you know by now that my documentary FINDING KUKAN revolves around my discovery of the “lost” 1941 Oscar-winning color film of war-torn China called KUKAN. Many of you might also be wondering, where in the H… is KUKAN? If it was found, then why can’t we see it? Well when I tracked down the only full copy of the film it had been sitting in a Fort Lauderdale studio for a few decades and then a Georgia basement for a couple more. Heat and humidity had done its work.

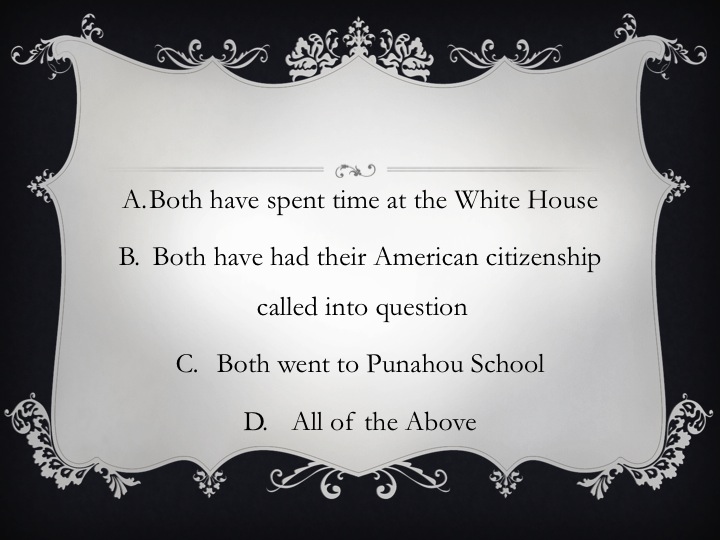

AMPAS documentary curator Ed Carter opens up the can containing KUKAN for the first time.

When AMPAS’s Ed Carter and Joe Lindner opened the rusty metal can that contained KUKAN they winced. “Vinegar,” they both said, wrinkling their noses. I learned later that that is a sure sign of deterioration. As Joe examined the 2 reels of film that represented 90-minutes of invaluable color footage of China in 1939 and 1940, he detected both shrinkage and brittleness (more bad signs of deterioration). Joe said he’d seen films worse off…but not many. Things looked pretty grim. If we were in the Emergency Room, this would be time for triage.

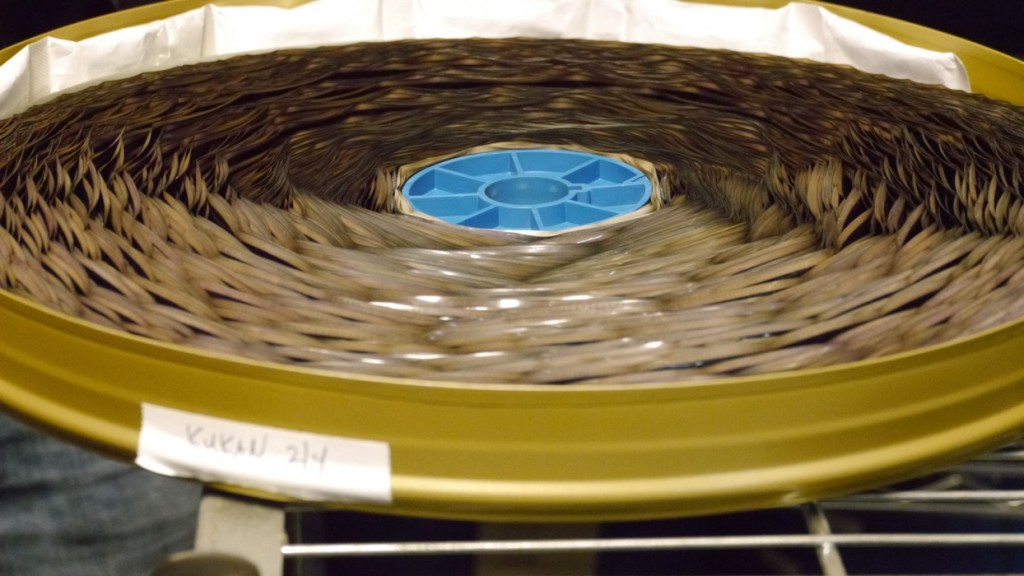

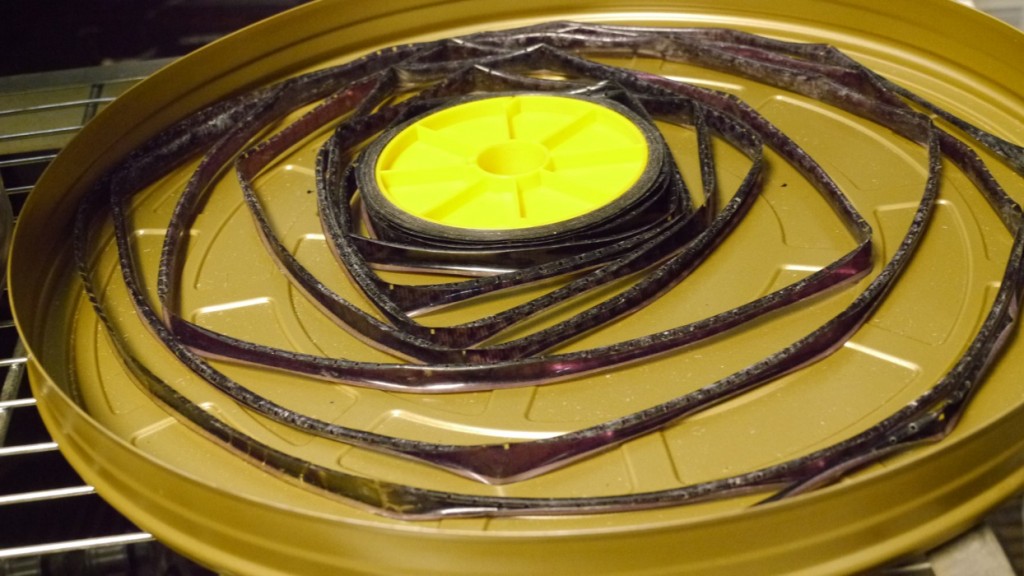

Fortunately a deteriorating film takes longer to die than a bleeding human. Two years later, KUKAN has been stabilized but is still in pretty bad shape as you can see by the photos I took of it last week at Colorlab in Maryland where AMPAS sent it to have major restoration work done.

One of the film cannisters that holds the only known full copy of KUKAN

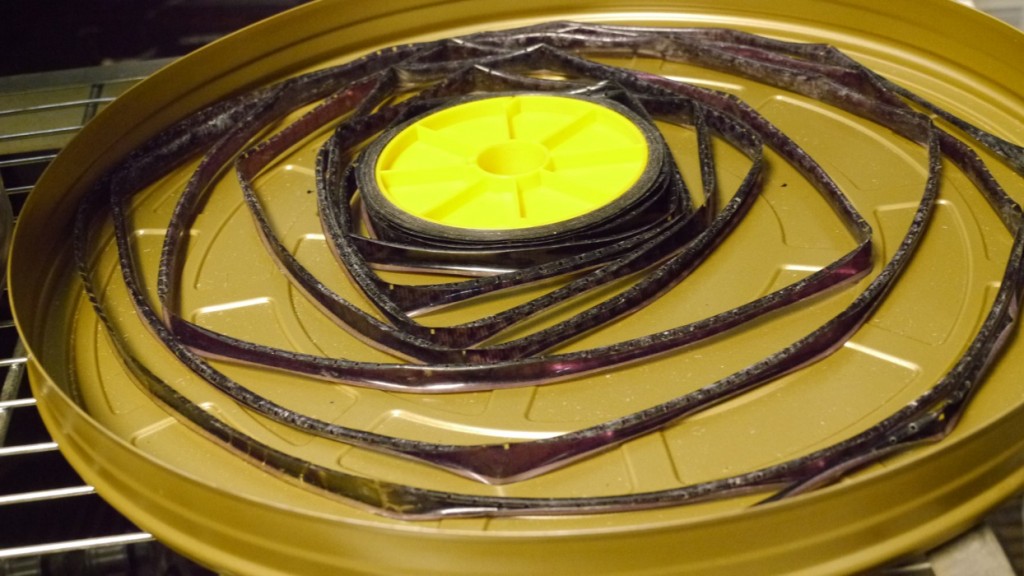

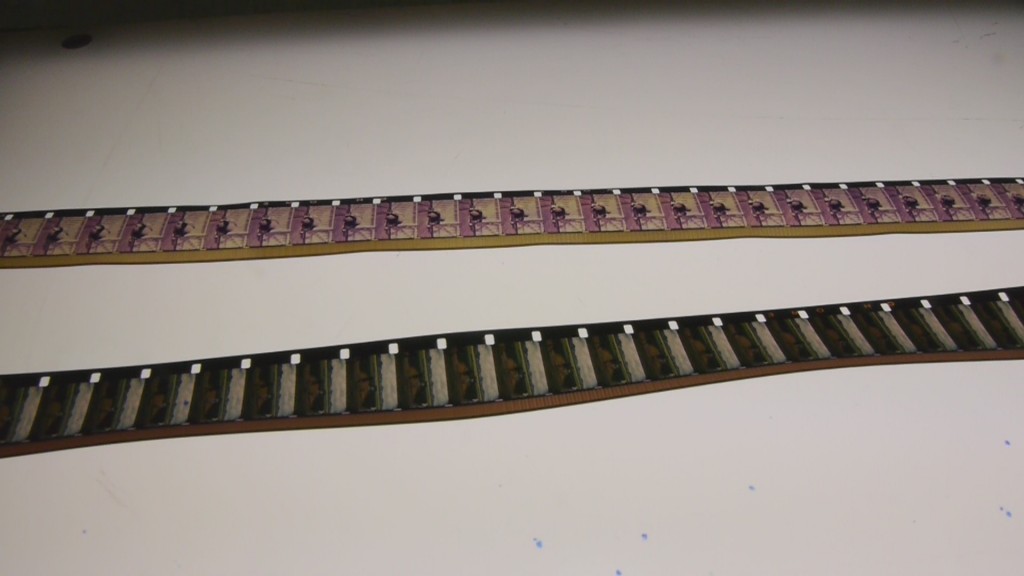

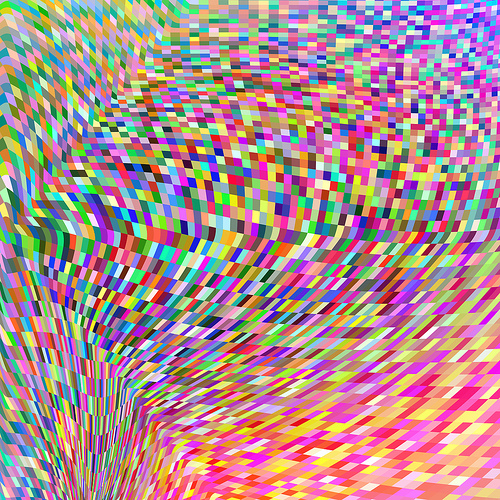

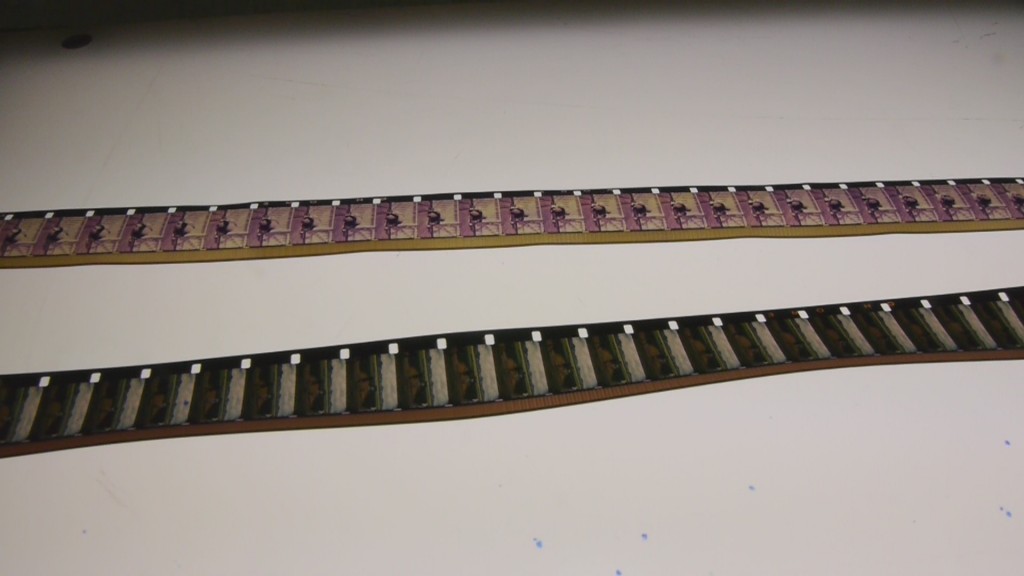

Close up of the shrunken 16mm film that contains some of the first color footage of China.

Parts of it are so curled that they will never be able to be re-plasticized (a sort of Botox process for film that hydrates it enough to allow it to lay flat in the scanner without breaking).

The worst part of the 2 KUKAN reels was so curled it looked like the plastic straws you drink out of.

A partial copy of KUKAN that I located in the National Archives (NARA) will be used to fill in those parts that are unsalvageable. The NARA copy was kept in a temperature controlled environment all these years and is in fairly good shape. But even that has to go through a frame by frame scanning process to pull both image and soundtrack from the 16mm strip.

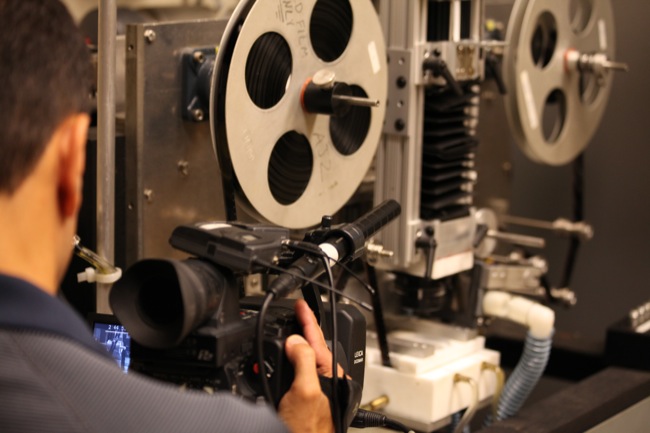

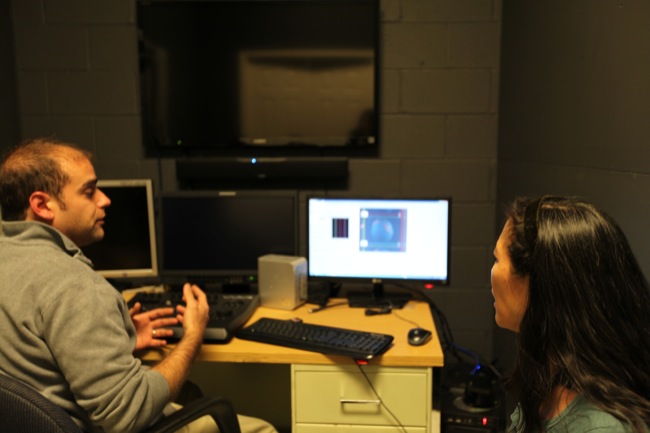

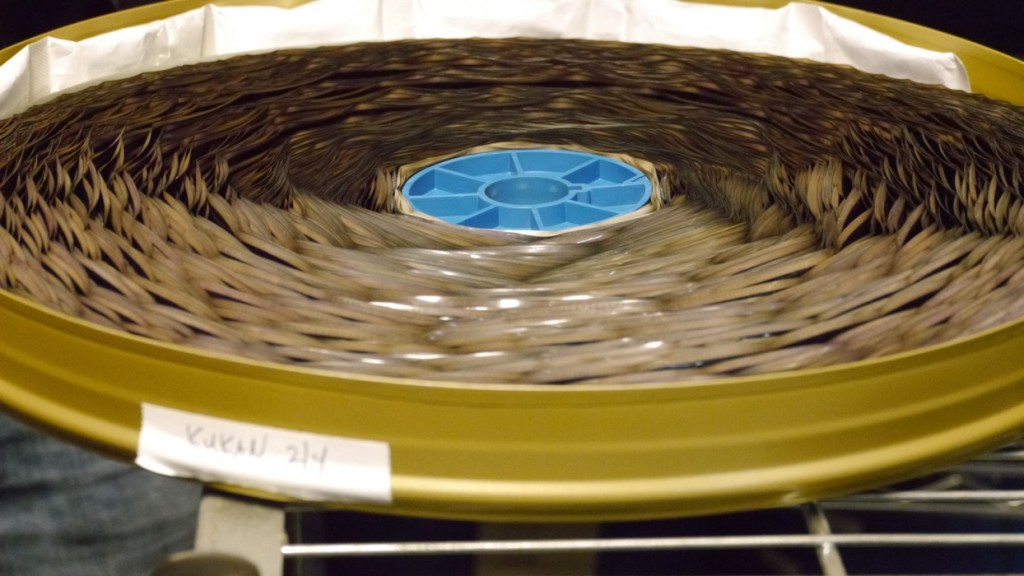

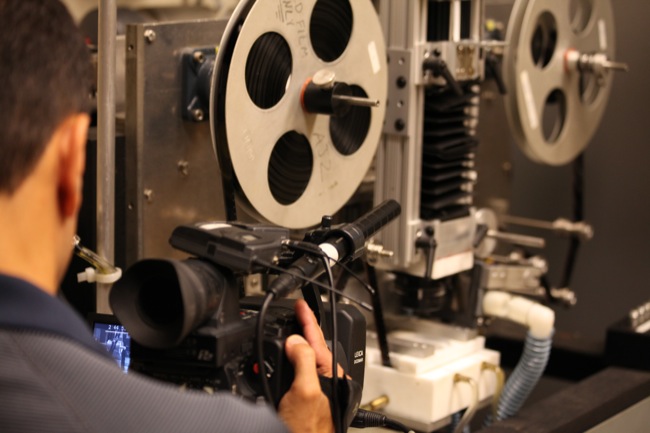

DP Frank Ayala shoots the scanning of a partial copy of KUKAN on the monster machine at Colorlab

DP Frank Ayala, 2nd Camera Mia Fernandez and I arrived at Colorlab to film the initial frame by frame scanning of the NARA print and learned a lot about the care and effort needed to bring a film back to life.

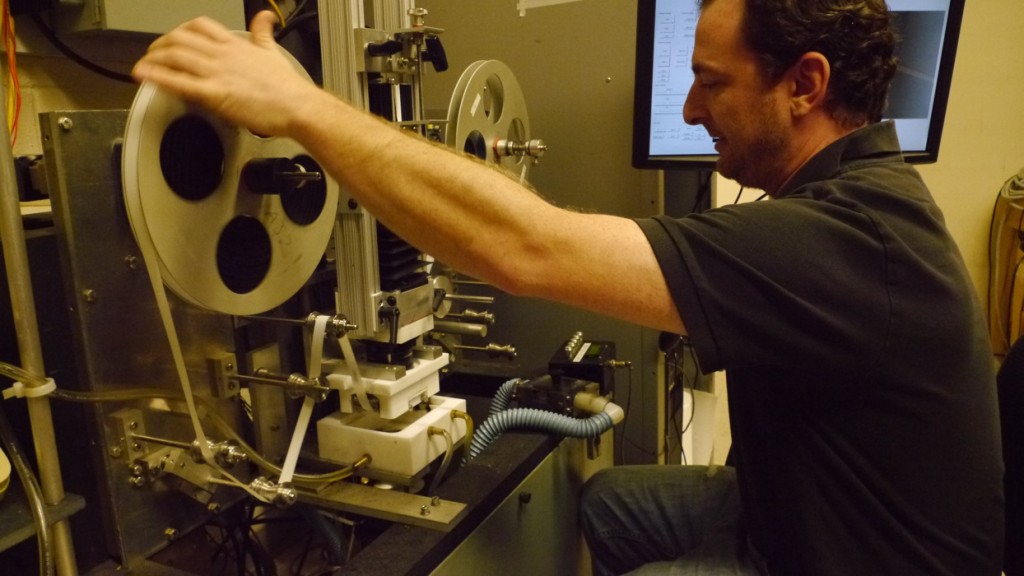

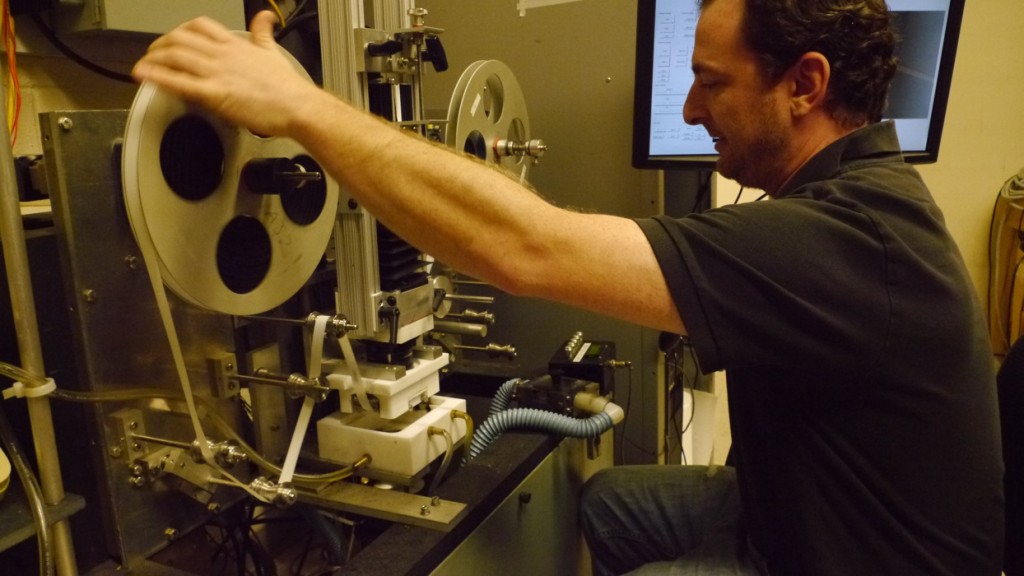

A.J. Rohner, project head on the KUKAN restoration, threads the NARA print through the scanner.

A.J. Rohner, head “surgeon” on the KUKAN restoration process, assured me that “my patient” could be saved despite its horrific appearance. He gave us a tour of the monster machine that does the scanning – an invention of Colorlab engineer Tommy Aschenbach.

The scanner doing all the work is a fascinating contraption that blinks and whirs and beeps — just like something out of Startrek.

I was entranced by its gorgeous parts, blinking lights and robotic movements — so much more tangibly satisfying to see at work than watching the little gray line creep across your computer screen as your digital footage downloads.

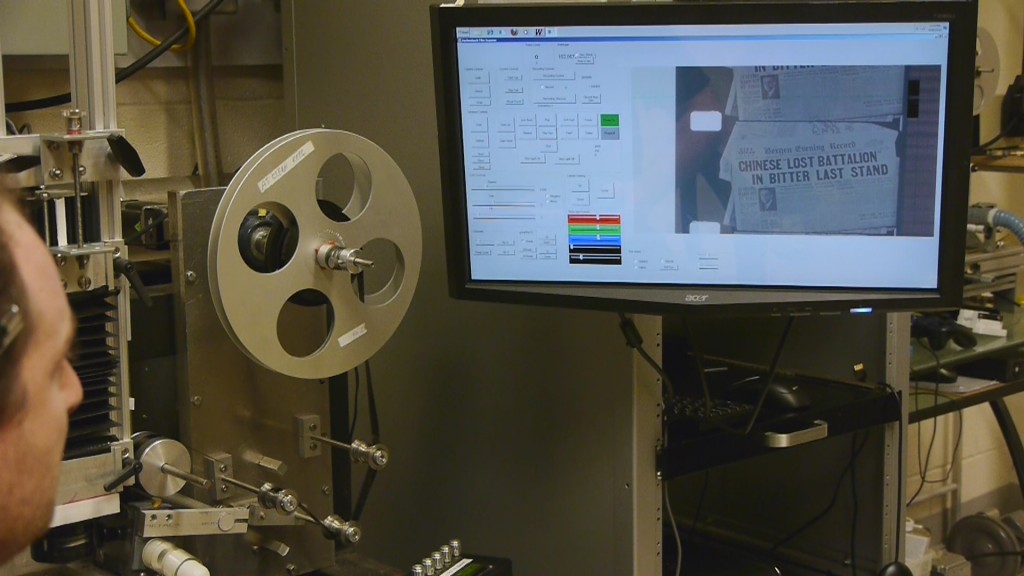

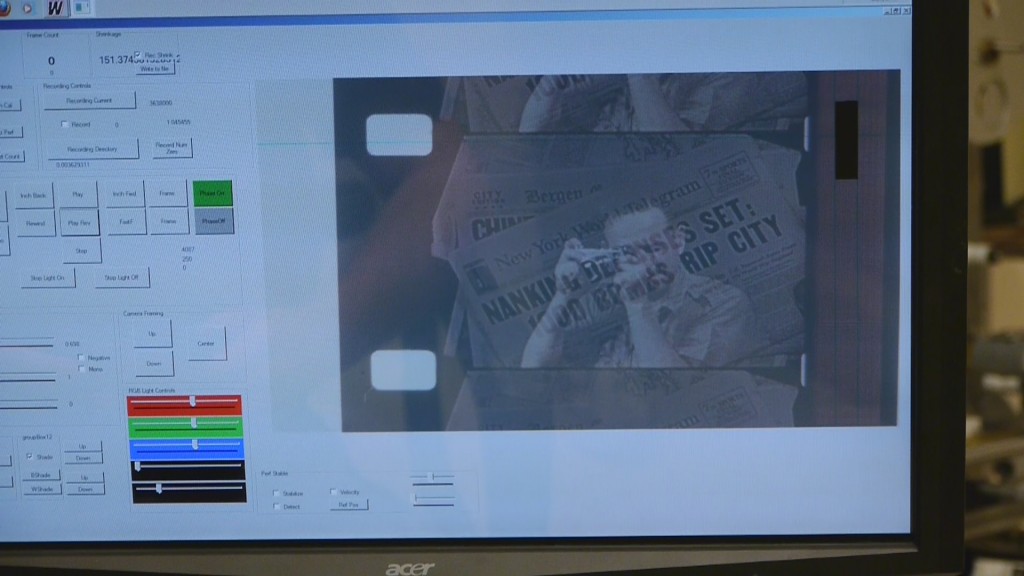

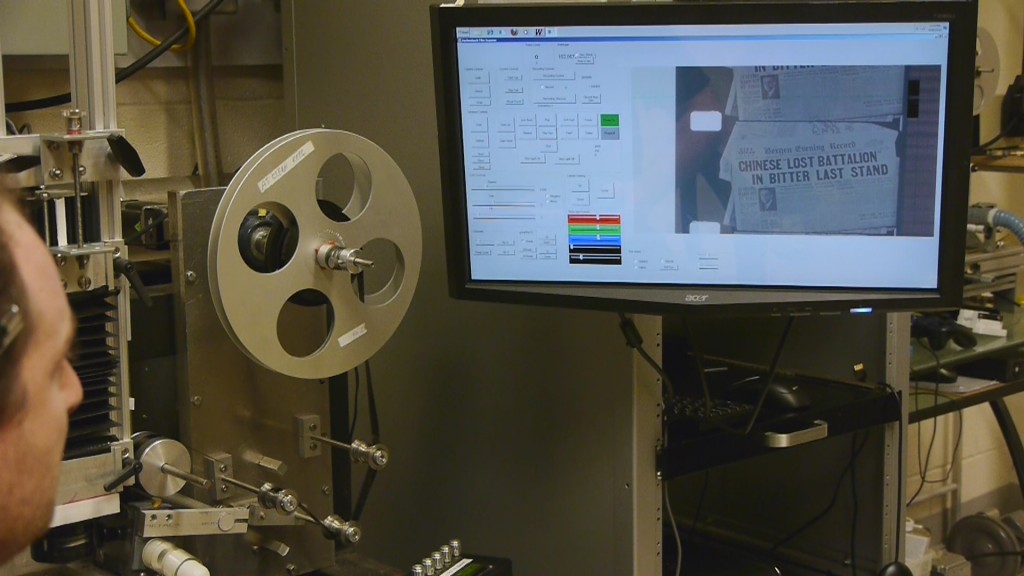

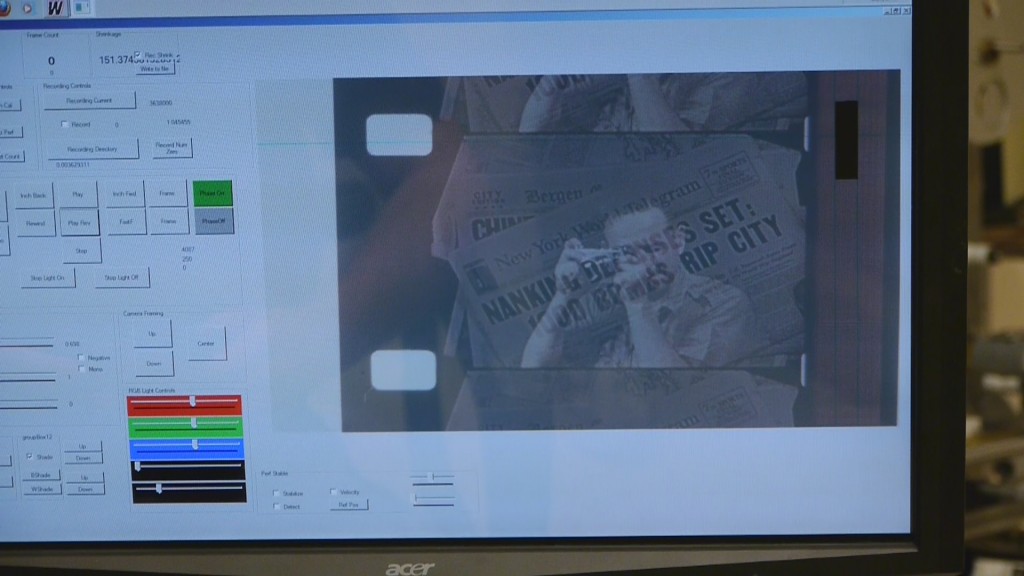

Frame by frame scan begins on the opening scenes of KUKAN

Rey Scott in one of the opening scenes of KUKAN

I also learned how the sound from the film will be lifted from the scan, VISUALLY corrected before turning into sound waves and then cleaned and scrubbed to get all the ticks, and hisses out. I was surprised to learn that those little horizontal lines on the edge of the film are what make the sound come alive through the projector – a magical phenomenon when you think about it.

Tommy Aschenbach demonstrates the magic involved in restoring sound on a film

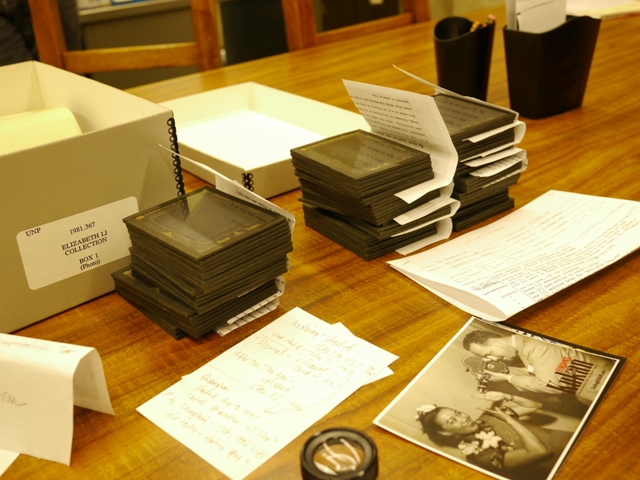

If you look carefully you can see the sound stripes on one edge of the film. The top strip is the badly deteriorated copy of KUKAN I found. Notice the color loss.

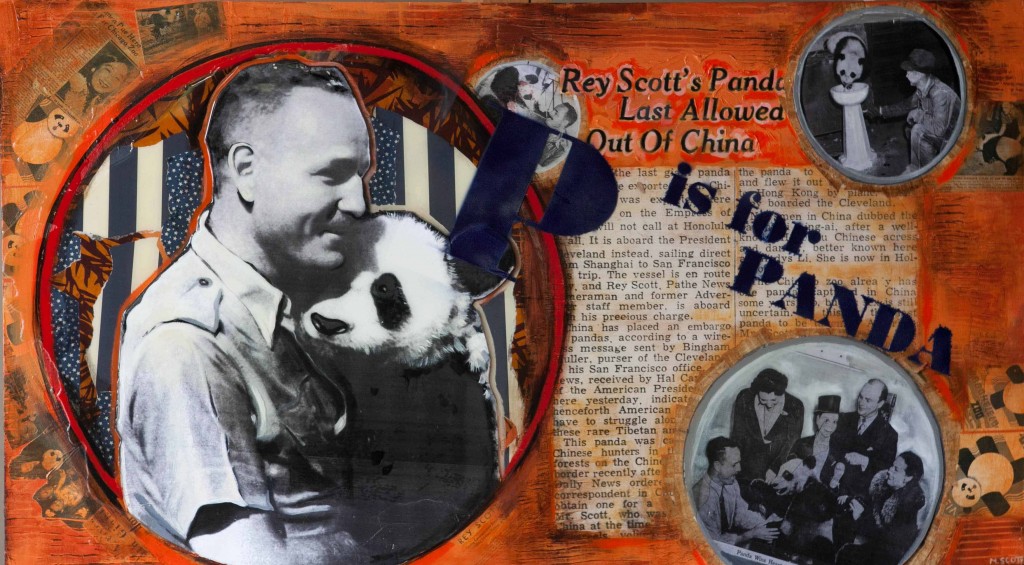

From the photo below A.J. identified the camera Rey Scott was using in China as a 16mm Bolex.

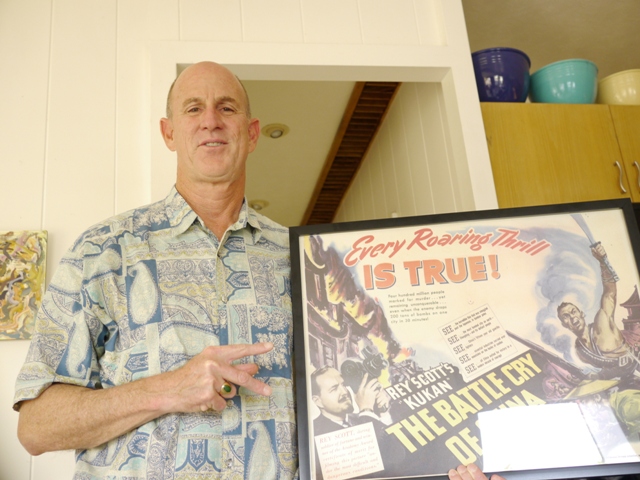

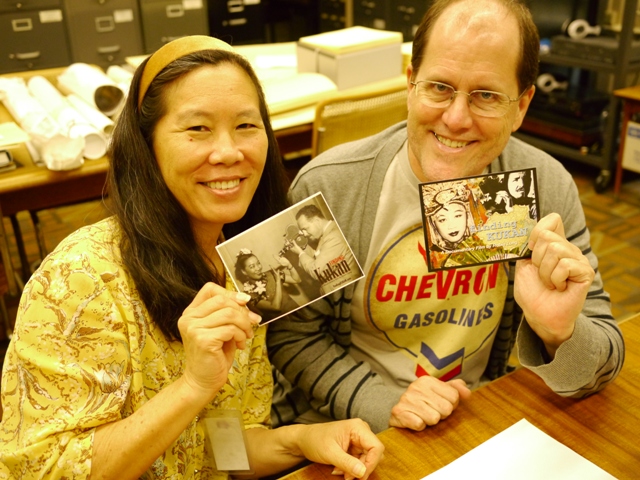

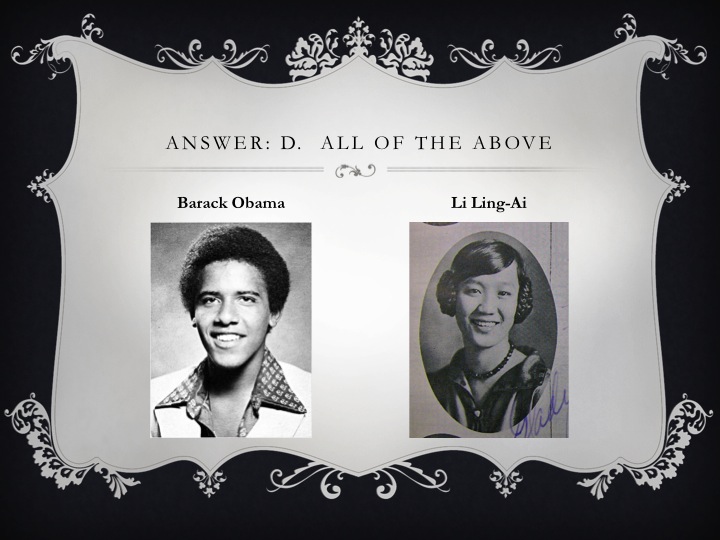

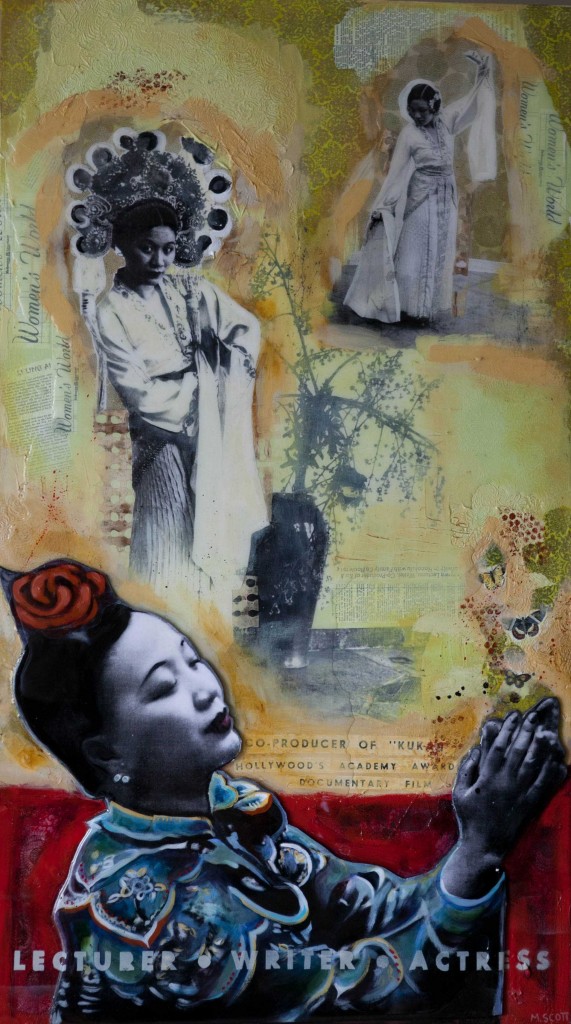

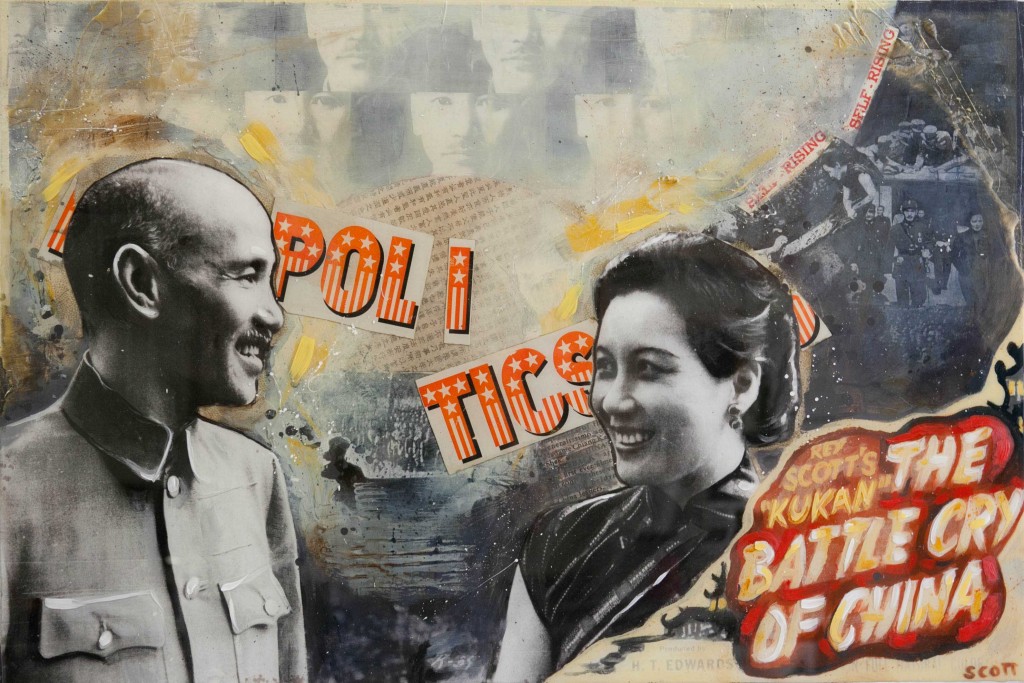

Publicity photo of Li Ling-Ai and Rey Scott taken in 1941

Colorlab technician Laura Major just happened to have one in the office that she still shoots with.

Laura Major demonstrates the workings of her 16mm vintage Bolex

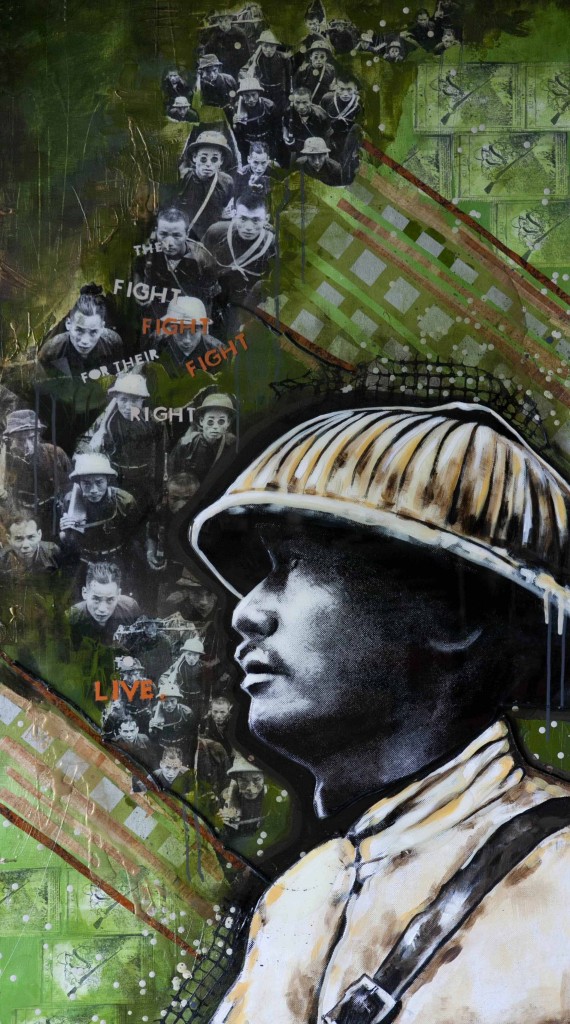

Holding that camera in my hands, looking through the tiny viewfinder, and learning that the camera could only shoot 100 ft of film at a time (roughly 2 minutes) gave me a much greater appreciation for Rey Scott’s heroic accomplishment in filming the epic scenes contained in KUKAN, especially the 15-minute sequence at the end of the movie that depicts the massive bombing of Chungking and the fiery destruction of the city.

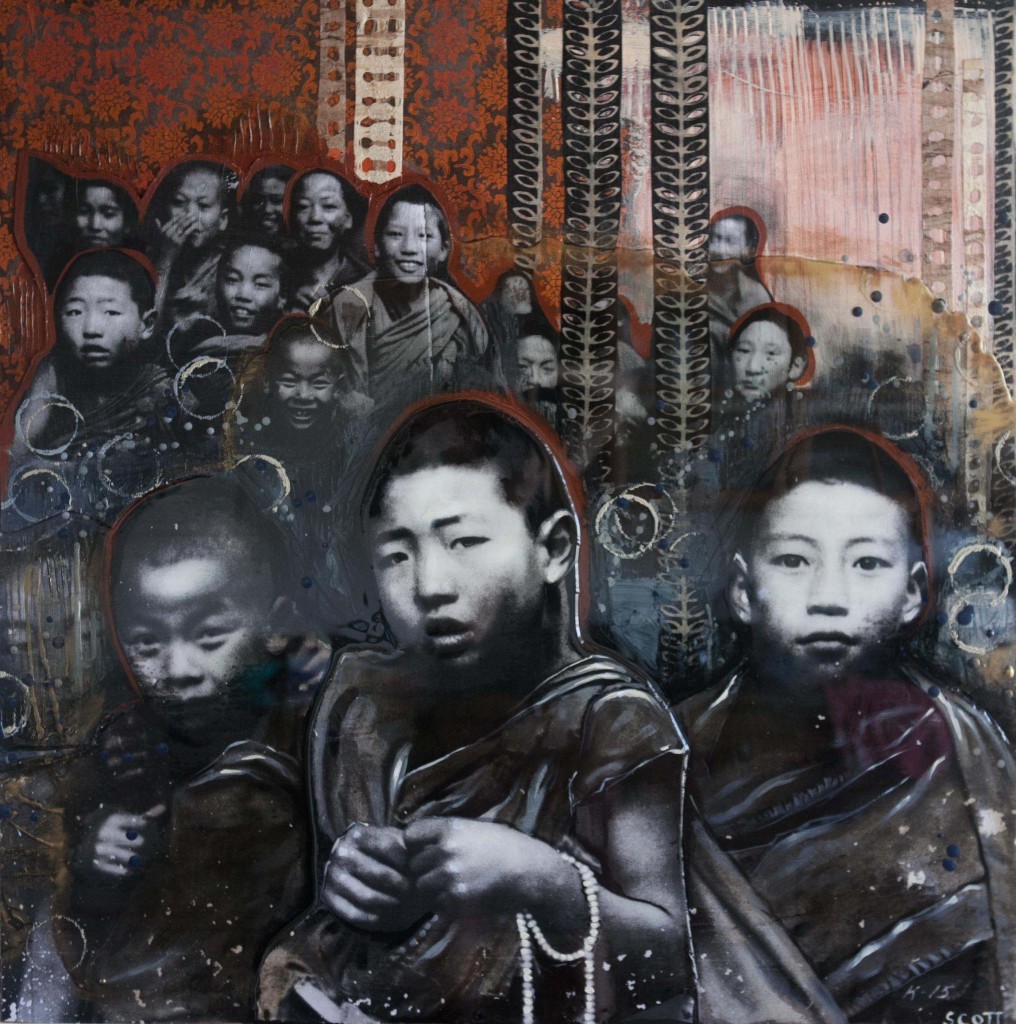

Chinese boy looks into Rey Scott’s Bolex on location for KUKAN

You can’t believe how tiny everything looks through this viewfinder — no wonder Rey had a hard time focusing in places.

I am more determined than ever to reach our $16,000 Kickstarter goal so that we can keep following the magical resuscitation of KUKAN and track the amazing story behind its creation. Please join me on this journey, it’s going to be an incredible ride!